The Wren and His Disciples

This is a story written in the style of a traditional medieval fable, in which animals and natural elements were used to convey lessons of morality. This particular story is meant to mimic what may have been a 1300's fable about one of the many European Christian inquisitions. No actual lessons of morality are meant to be given here— this is an educational exploration blending research and fiction in order to explore a historical topic. After the fable is a brief summary of my research, including the history of the inquisitions and the symbolic significance of the animals represented in this story.

The Fox, the Crow, the Lamb, and the Panther

A Wren flew into a densely populated area of the forest, closer to the ground than the Wren would normally fly if not on a mission. The ground animals were not used to seeing such birds as the Wren fly so close to the ground, so they naturally gathered around him to inquire upon the occasion.

“Sir Wren,” a brave Rabbit started, “what are you doing down from the high branches of the trees?” The Wren looked at the simple Rabbit warmly and, puffing itself up, declared loudly, for all the curiously gathered animals to hear, “Hello my dear ground level friends! It’s been so long since my last visit down to the earth; how I miss it here! When up in the high trees, how easy it is to forget that this world is founded upon the hard work and diligence of all those on the lower level! I am truly humbled to have you accept me into your grounded society. Pray, good Rabbit sir, is the town Partridge in?” The animals, all thoroughly impressed and flattered by the Wren’s kind words, turned back to the Rabbit. Rabbit, seeking to impress the Wren who singled him out for importance, turned to the nearest youth and sharply instructed: “Go fetch the Partridge.” As the Bunny ran to the Nest, the Wren continued to talk with the forest folk. He inquired into how they enjoyed life on the ground and gathered information on the prominent animals of the area. When the Partridge arrived with the Bunny, the Wren thanked the youth and went off alone with the Partridge.

“To what do we owe this visit, Wren?” the Partridge asked.

“The birds of the high branches have been twittering about one young Fox who is said to be causing trouble down in this area. They sent me to find him and ask some questions.”

“You think this is a heresy matter?” the Partridge pressed.

“It is possible. I can say no more until we find the Fox in question, and speak with him.”

“I know where his den is; we can go immediately.”

“Good. But first,” the Wren said, extending a small wing in front of the Partridge, who had already begun to hurry off to the Fox’s dwelling, “I don’t believe you are properly schooled in the inquisitorial matters. We are dealing with a dangerous heretic, do you understand?”

The Partridge nodded enthusiastically, but thoughtlessly. The Wren knew he would have to spell things out plainly for the common bird.

“This issue is bigger than you, and bigger than the Fox, and bigger than even myself. These simple ground folk believe they know the complexities of our Holy Lord Dove, but they are easily misled by proprietors of false knowledge and practices. Such heretics as the Fox are a menace to our society, as he has endangered every soul that falls into the trap of his false promises. You must be the performer of good against his performance of evil and root him out of society if he is spreading a false truth.” The Partridge again nodded, appearing to comprehend the importance of the Wren’s job, and off the two flew to the Fox’s den. Upon arriving at the den, the Partridge stood diligently outside while the Wren went inside to chat with the Fox. After hours of quiet, pleasant conversation, the Wren handed the Fox a paper with instructions to appear at the Nest of the Holy in one week’s time. The Wren exited, and the Partridge excitedly hopped after him.

“What did you ask? Is the Fox guilty?” the Partridge asked.

“The questions are only to be known by the Inquisitors,” the Wren responded haughtily, “and of course he is guilty. When the birds of the high branches start chirping “Heretic,” are they ever wrong?” The Partridge earnestly shook his head. “No,” the Wren continued, “I thought not.”

As the two continued on, they passed by a white bird giving a sermon to a crowd of animals. The bird screeched with the name of the Dove and squawked with promises of salvation, but he did not appear to be a true bird of the Nest. As the Wren and Partridge drew nearer, the Wren noticed with horror the flash of dark feathers under the white exterior. In a flutter of wings the Wren was over the crowd of listeners and perched above the “white” bird, who had now stopped his preaching and stared curiously up at the livid Wren.

“Animals of the forest,” the Wren loudly started, “you think you are being led by a bird of white, white that is granted by the Holy Dove to only the most sinless and blameless birds of the highest branches, but this bird before you has deceived you! This is no bird of white, but rather a Crow, as black as the Blackbird himself!” Wren dramatically ripped off the plume of white feathers covering the Crow’s black ones as a gasp emerged from the congregation. The Wren continued vehemently, “this heretic has been spreading the Blackbird’s message masqueraded as the Dove’s, and he has put you all in danger. He is an imitator and falsifier and he debases the real word of the Dove. He uses Scripture for his personal gain and manipulates you to his own sect, not to save your souls.” Thoroughly frightened, the animals began muttering about this Wren, this stranger who has come in suddenly and uncovered one of the town’s most holy followers of the Dove as a black-feathered Crow. The Wren handed the Crow a paper to appear in the Nest of the Holy in a week, and without another word flew off.

In the week leading up to the trial, the Wren stayed with the Deer family one night, the Chipmunk family the next, the Boar family the next, and so forth. On the fourth night, the Wren stayed with the Sheep family: a deeply religious family. As the Wren, the Ram, the Ewe, and the Lamb sat around the table that night after supper, the Lamb quietly excused herself from the table and disappeared up the stairs. The Wren inquired curiously about the quiet nature of the young Lamb, and why she had barely spoken a word or cast a glance at the Wren since his arrival. The Ram and Ewe looked at one another nervously, and admitted to the Wren that they were worried for their Lamb.

“Something has been off about her lately,” the Ewe started.

“That’s right,” the Ram chimed in, “she has stopped coming to sermons with us when it used to be a favorite pastime, she hardly touches her food, and every night after dinner she retires silently to her room.”

“What does she do up there?” Wren asked.

“We haven’t the faintest idea,” Ewe admitted, “when we ask, she just looks away, as if in a mist. We’re worried for her, Wren, worried something has led her astray.”

“The same thought has crossed my mind,” the Wren admitted, “I shall talk to her. Will you please fetch her from upstairs? I want to ask her some questions.” The Ewe immediately trotted upstairs, and after a couple minutes returned with the small Lamb, who silently sat across from the Wren. The Ram and the Ewe started to take a seat next to the Lamb, but the Wren stopped them with a raised wing. “If you please,” he began, “I’d like to speak with her alone.”

After about an hour passed, the Wren emerged from the sequestered room and met with the flustered parents. They immediately asked what had happened, and he shushed their questions with a sheet of paper instructing them to come to the Nest of the Holy in three day’s time. The Ewe took the note from the Ram’s hoof and asked what this was about, and what had happened to their daughter. To calm the frantic Ewe, the Wren calmly stated that the Lamb has been misled by the Blackbird and his evil ways, and she is certainly down the irredeemable path to the Dark Forest. The Ewe began to cry, while the Ram turned to comfort her with suggestions of taking their Lamb to the Panther. Upon hearing this, the Ewe’s tears slowed, and she resolved to go immediately. “Pray tell,” the Wren interrupted, “who is the Panther?”

The Ram accompanied the Wren to the house of the Panther as the sun set over the forest and the shadows grew long and foreboding against the ground. The Wren had insisted the Lamb and Ewe stay home, as much as the Sheep family argued. Now as the Ram and Wren walked together along the dark path leading to the home of the Panther, the Ram told the Wren of the powers of the Panther.

“She’s well loved by everyone of the community,” the Ram informed the Wren, “because she can cause miracles to happen simply by her breath.”

“How,” the Wren demanded sharply.

“No one is quite sure,” the Ram continued rambling, “but she must draw her powers directly from the Dove above. She even sleeps in the trees like the birds to be closer to Dove, that is how great her power is. She is revered by our community, you will be very impressed by her I’m sure.”

“Yes,” the Wren squawked hesitantly, “I’m sure.”

As they arrived at the Panther’s tree, the Ram began to shout up to her, only to be quickly hushed by the Wren. “I shall go up and meet her,” the Wren told the Ram, “thank you for leading me here. You are free to go.” The Ram started to protest, saying he had to talk to the Panther for advice on his Lamb, but he was again silenced by the Wren. “You do not need any opinion other than the opinion of the Dove, who has spoken through me. Be at the Nest in three days and everything will be explained to the community as a whole. But for now, go home and leave me to do my duty.” The Ram considered protesting again, but gave up and slunk back home. When the Wren was sure he was out of earshot, he flew up to the Panther’s branch.

The Panther was lazily slung across a branch midway up the tree, with her head on her paw. “I know why you’re here Wren,” she yawned, trying to open her mouth as wide as possible to show the Wren how small he was by comparison.

The Wren, unaffected, spat back, “I’m sure you do. Do a lot of consorting with Blackbirds, do you?”

The Panther looked back to the Wren and slowly blinked and laughed. “I haven’t done anything wrong Wren,” she asserted.

The Wren chirped forcefully and asserted with confidence, “I’m sure I can find some testimonies otherwise. You can’t hide in the shadows forever Panther, the light will shine on you too and expose your sins to all.”

The conversation ended with another fateful slip of paper.

~

Every animal that could fit in the Nest of the Holy packed in and covered every rock and branch available. Little animals stood atop their neighbor’s heads and shoulders for a better view, and the whole area was a flutter of wings, hooves, and paws. The Fox, the Crow, the Lamb, and the Panther stood solemnly at the front of the congregation. All came to a quick hush when a flock of tiny Wrens flew down from a high perch and settled in their places at the front center, with the Partridge standing to the side. The Wrens chirped among themselves for some time, while the rest of the animals watched curiously and the Partridge strained to overhear. After some time, the original Wren turned to the congregation and, in as loud a voice as he could muster, demanded: “Quiet down, and let the proceedings begin.”

The lead Wren then proceeded to squawk and caw in the language of the birds that most of the animals in the room could not understand, but they recognized it as an important language of the Nest. The Partridge and collection of Wrens nodded along thoughtfully, while the rest of the animals waited for the vernacular version of the hearing. Then the Wren started:

“We will start with the heretics of the last hearing. Frog, you are hereby permitted to drop the branch you have bore for the past year. Goat, you are now freed from your imprisonment and you will now take up a branch and bear it for the next four years to show your repentance. See these two sinners forgiven: this is the power of the Nest and of Dove above. The Nest is a place of repentance and mercy. May you never strive from the path into the highest holy branches, and never again let yourselves be tempted by the calls of the Blackbird into the Dark Forest. May Dove watch over you all. Now to the heretics found guilty in this hearing. Fox, step forward. You have been found guilty of heresy through the spread of false knowledge. You proclaim to be a graduate of Foxford University, yet you seek to lead animals astray from the righteous path by spreading knowledge you know to be false. You do not honor Dove and the sacred texts, so you are hereby sentenced to take a penitential pilgrimage and pick up a single branch to show your repentance. Step back.

Crow, step forward. We-” gesturing to the small flock of Wrens with a small wing, “have found you guilty of heresy by spreading the word of the Blackbird under the cloak of the Dove. You seek to use the words given to us from above for your own personal gain and manipulation, and you stand as not only a threat to your own salvation, but more importantly a threat to your community, as you threaten the lives and salvations of every animal who is poisoned by your false words. You shall be put in front of all with your beak painted red to show to the public that the words from your mouth are false and evil. After you stand for four days publicly displayed, you are sentenced to imprisonment. Step back.

Lamb, step forward-”

This caused a low murmur to echo through the congregation, which was hushed with a sharp glance from the Partridge. The Wren continued without hesitation:

“You are found guilty of heresy and being led away from Dove by Blackbird forces that have taken over your mind and body. By refusing to answer my questions or confess during the inquisitorial period, you have proven your own guilt beyond any doubt. The Blackbird holds your tongue from speaking or acknowledging an agent of the Dove. You no longer attend Nest sermons because the Blackbird inside of you cannot bear to hear the words of the Holy Dove. You do not eat because the Blackbird within you needs no earthly nourishment. For this offense, you are sentenced to life imprisonment, and your house shall be burned to purify it of the influence of the Blackbird that has taken root there. Step back.”

The Lamb let out a small tear and quivered as she stepped back into the line of the accused. An angry Rabbit, who had always been good friends with the Sheep family, yelled, “This isn’t right!” He was quickly quieted by those around him, and the Partridge haughtily responded, “there are no mistakes in the Nest of the Dove.” The Wren ignored the outburst, and continued with the final judgment:

“Panther, step forward.”

Again, a murmur, louder than the last, erupted through the crowd. Though the Partridge tried to hush the congregation, whispers of why the Panther and the Lamb were up with the guilty and questions regarding the authority of the Wrens and the truth of these hearings spread through the crowd. The Wren sharply raised a small wing without even looking at the congregation, silencing the animals.

“You have been found guilty of heresy through the allegiance with agents of the Blackbird. You have been practicing wrongful healing, as by your being a feline there is no way to gain the knowledge you appear to possess without either spying on practices illegal to your kind or consorting with Blackbirds. The heresy you embody has been spread through the community by your illicit practices, and the influence of the Blackbird lies too deeply rooted in your soul for any hope of redemption. Therefore, as the destruction of heretics is the true goal of the inquisitor, we must seek to thoroughly destroy the receivers and defenders of this heresy. Heretics are fully converted only after two processes: firstly they must fully accept Dove and the light of the High Forest, and secondly the Blackbird must be burned from them.”

This sent the congregation into another flurry of chattering and chirping, which was loudly talked over by the Wren, who continued:

“However, as a member of the Nest, I am not permitted to shed blood, so I will not be burning the Panther.”

A relieved hush fell over the Nest, allowing the Wren’s next words to echo in the minds of all present:

“I will be giving the culprit over to the secular authorities, who will see the Panther is burned alive. Step back. May the Dove watch over you all.”

The Nest erupted. Many animals protested the Wren’s judgements. Some animals comforted the Sheep family and cried for their loss of a young Lamb. Other animals yelled that they cannot leave the Panther, the town’s only healer, to burn. Still other animals nodded their heads in agreement and yelled about how the Wren was correct in his judgements, and the heretics deserved their punishments. The Nest was deeply divided. The Partridge, worried about the explosive commotion, flew up to the lead Wren and whispered, “Should we do something sir?”

The Wren hardly seemed to notice the riotous community behind him, and calmly stated, “This is the work of the inquisitor. No consensus can be found among the common ground folk, so we must show them the collective consciousness that we want them to adopt. This consciousness must be the strict adherence to the word of the Dove and the strict alienation and damnation of all heretics. Heretics are social dangers, and the ground animals are too simple to recognize them on their own. That is why we must fly down and bring them into the light before they continue their harm. That is the purpose of these inquisitions. Any method necessary is rectified by the end purpose: the destruction of all heresy. We will destroy the heretics and destroy their houses and destroy their families and friends and purge their words from this Earth. Such is the price we must pay to root out heresy, which threatens the branch our entire world is founded upon. Let them complain; they do not know any better. But you and I, we are the masters of the sky. We understand the Dove and the ways of the high branches. We know the way of the Nest. So we must find them, punish them, and, if necessary, let them burn.”

Animal Symbolism

Each animal in The Wren, the Fox, the Crow, the Lamb, and the Panther has a medieval Christian/Catholic symbolism.

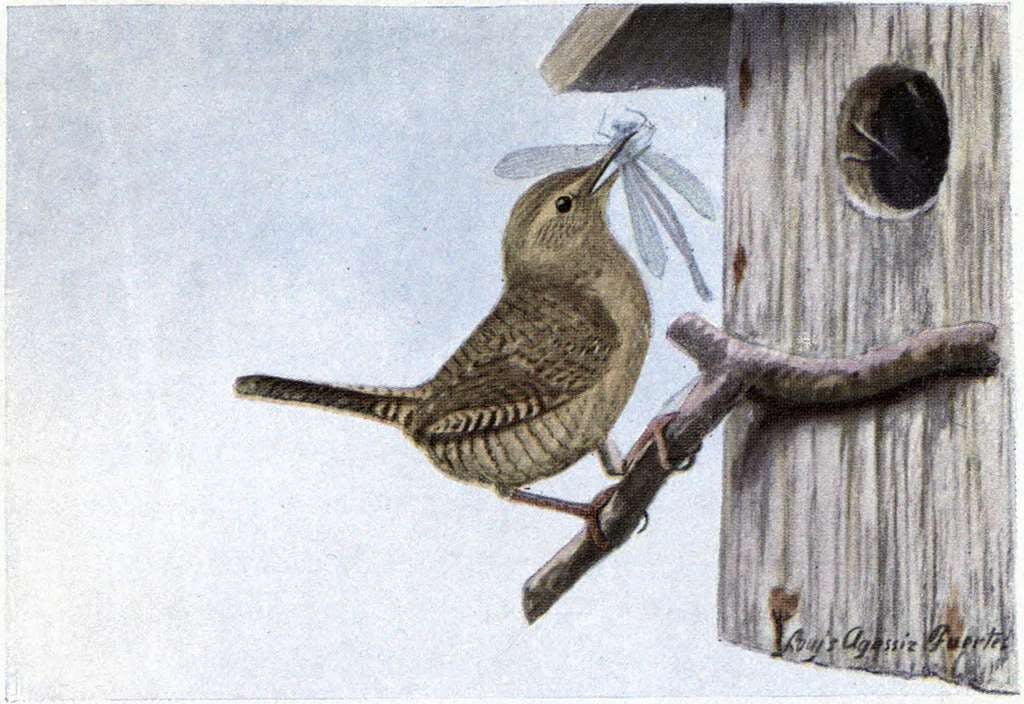

The Wren has been paralleled with powers of prophecy, and I chose this bird for its small stature and the splatter of white feathers on its face, which in a world where white birds are the closest to divinity (Dove), can be seen as a mark symbolizing the Wren’s purity. However, a Wren is mostly mottled brown, so any white plumage it has would be greatly over-signified. The character of the Wren is based heavily on Bernard Gui, a Dominican friar known for his involvement as a papal inquisitor during the later stages of the Medieval Inquisition. The dialogues about acting curious to uncover heretics, uncovering those masquerading as holy men, the ends of an inquisition justifying the means, and the only two ways to stop a heretic through conversion and burning are very similar to Gui’s own writings.

The Partridge is sometimes a symbol of the Church and of truth, but more frequently it is a symbol of deceit and theft. As a little brown bird, again with the smallest bit of white facial plumage, it seemed the perfect choice for a town Bishop, who often accompanied the inquisitors after the year 1317. Many clergymen even today want to believe they stand for truth and the Church, but their actions all too often fall to the side of theft and deceit instead. It is always easier to find the heresy in others before admitting one’s own sins, and this hypocrisy and readiness to condemn the actions of others inspired me to represent the Bishop through the Partridge.

The Fox is famous for pretending to be dead and unthreatening to ensnare unsuspecting prey, like the Devil deceiving unwary souls. However, the Fox is also confident and cunning, and uses his knowledge to his own benefit. The Fox, therefore, seemed the best option to represent the threat of misinformation in society, which became an issue after the formation of universities, which made knowledge much more publicly accessible.

The Crow is another prophetic bird, but it is traditionally thought that the Crow only induces anxieties by spreading false prophecies. Black birds also commonly represent sinful souls, so the black Crow masquerading as the white bird would have been exactly how the church saw heretics who pretended to be upright Christian citizens, but were truly heretics in disguise. When the Crow is sentenced to have his beak painted red and to be publicly displayed for a certain number of days, this is a nod to the practice of sewing red tongues to the shirts of heretics and forcing them to be publicly displayed before their imprisonment.

The Lamb is a very traditional symbol for innocence and purity and is frequently represented as the sacrifice for sins. Even though there existed a deliberate system of finding people guilty, the Inquisitors of this time were so caught up in rooting out all heretics that it was easier to find everyone guilty of heresy, including many who were not engaged in any sort of heretical act. After an inquisitor questioned a suspected heretic, there was a grace period allotted for the heretic to confess everything, but the person was not made aware that they were suspected of heresy. The heretic was assumed to know of their heresy, and so it was assumed that they should be ready to admit to their heresy when confronted by the inquisitor. To not answer the inquisitor’s questions was seen as trying to hide the truth, and was therefore treated as a guilty confession.

The Panther is an interesting and less recognized medieval symbol. In traditional medieval stories, the Panther embodied tameness and gentleness and was thought to be loved by everyone in the community except for the Dragon, who frequently represented Satan. The breath of the Panther was like the touch of Jesus Christ, and it could heal any animal except the Dragon, who was repelled by the Panther’s breath. I thought this would be an interesting nod to witchcraft as heresy, which was the focus of later Inquisitions, despite witchcraft often simply being an early form of medicine.

The Blackbird is often used as a symbol of temptation, sin, and a representation for the Devil. The Frog is a symbol of life’s worldly indulgences and the Goat is a symbol of fraud and lust, so these were the two creatures representing the past heretics. In the real inquisition trials, after going through the punishments of the live sinners, Gui would then go to the punishments of the deceased, who could also be subject to a post-mortem fire. The Fly was a character I decided to leave out in the end, but is a symbol of sin, pestilence, and disease. Since flies have notoriously short lifespans, I thought it would be a nice nod to the fact that not only sinners who were still alive were punished in these proceedings.

All public inquisition trials were first given in Latin, and then retold in the common vernacular of the town, which is why the Wren begins the trial in the “language of the birds.”3 The branch that some of the animals must pick up or wear is the cross, which could also been seen as a way in which non-flying animals could climb upwards towards their God, the Dove.

The Inquisition Proceedings

Multiple inquisitors were needed to give a trial and come to an agreed upon punishment for a heretic, though I decided to focus on the actions of the lead inquisitor. Inquisitors were not called upon by the people of the village, but rather sent down from a high ranking church official. The church officials frequently sent monks to act as inquisitors because they were religious men who were not bound to a cloister, and so they had the freedom to travel from village to village. Bernard Gui described himself as a performer who put on an act for the audience of the town against another performer: the heretic. He was very fond of theatrics and making the inquisitions into dramatic spectacles to emphasize the importance of rooting out heresy. Universities, which were still rather new institutions at this time, were places of controversy over heresy, orthodoxy, and spiritual authority. Universities produced a variety of learned men, some of whom became inquisitors themselves and others who opposed the inquisitions. An educated man who opposed the work of the church would have been seen as a heretic, but often the punishments were often lighter since they were protected under ecclesiastical law. Gui describes heretics as people who mask themselves as supporters of God, and may believe that they are supporting God, but are doing so in an incorrect manner. Inquisitional questioning was done in private, and the accused was lawfully required to answer all of the inquisitor’s questions. Therefore, not answering the questions and heretical responses were treated with the same level of condemnation. People naturally tried to create a positive image for the inquisitor, who was an incredibly high-ranking and respectable figure in small villages, which sometimes led the inquisitor to assume false guilt. My focus in this fable was to describe the Inquisition before it focused on witches and witchcraft, with only a hint to the severity with which inquisitors like Gui would have dealt with witchcraft, which was considered an extremely dangerous social threat.

While the questioning of the heretic and the trials to determine guilt were done in secret, the punishments of the inquisition were meant to be a very public spectacle. At this time, there was no public demand to root out heresy. Some villagers hated those punished and viewed them as enemies of God, while others deeply sympathized with the condemned and perceived them as innocent martyrs. In cases like the Lamb, in which a well-known person was punished for not answering an inquisitor’s questions, the public tended to side with the accused rather than the inquisitors. Trials were frequently begun with pardoning past heretics in order to show the mercy of the Church, and then followed by the condemnation of those newly found guilty.

The book Inquisition and Medieval Society: Power, Discipline, and Resistance in Languedoc contains a record of Bernard Gui’s punishments and how many people received each type of punishment. Punishments were given out based on the severity of the offense, and ranged from a penitential pilgrimage to being burned alive. Wearing a single or double cross or taking a mandatory pilgrimage was given to people who were convicted of minor heresy or who readily confessed, while death by fire was reserved for those considered to be the most dangerous heretics. Despite Gui’s passionate hatred of heretics and desire to destroy not only the heretic, but also anyone who received or defended the heretic, very rarely were people condemned to the flames. By far the most common punishment was imprisonment, with the next level of extremity being imprisonment paired with burning down the heretic’s house. Those who were found guilty of trying to spread their heresy to their community were often publicly humiliated as their punishment, in order to try to rally the townspeople against the supposed heretic.

In Gui’s mind, the theatrics of the inquisitions were meant to save people from the threat heretics presented to their communities. In making the punishments as visible as possible, inquisitors were trying to establish a collective conscious of the masses that was never able to be established, as people continued to oppose the inquisitions as much as others approved of them. This societal panic over “community threats” is as ingrain to humans as suspicion and anxiety. Blaming the ills of the world on a scapegoated group, with the promise of ridding a community of evil by removing them, has been a fear and manipulation tactic used by powerful ruling classes for centuries. This is a dangerous theme seen throughout history into our current world, but examining the history of these tactics gives us crucial insight into these patterns of behavior and alerts us to the repetition of the same rhetoric used since medieval times.